DEC. - Vol. 1, No. 4

In memory of Justin Byun….

New!-

Snickers

By: Abegail Byun

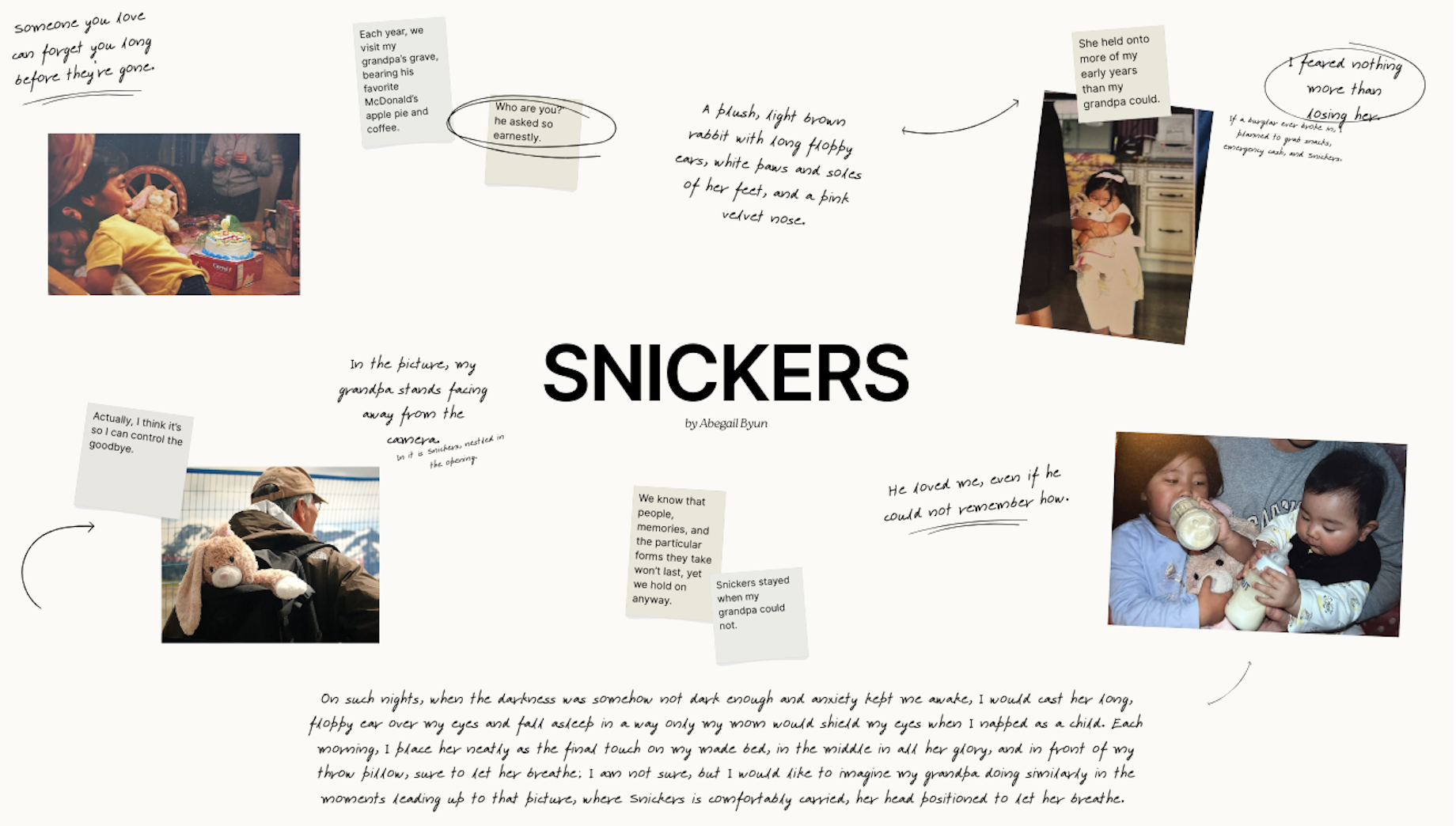

It’s been ten years since my grandpa passed away. I am not sure whether that, or the fact it can now be called a decade, is more surreal. Each year, we visit my grandpa’s grave, bearing his favorite McDonald’s apple pie and coffee. The grass is frosty that time of year, I am home for Thanksgiving, and my family gathered around his headstone. I sip on the coffee, each time shocked that it’s shittier than I remember, and I attempt to feel moved.

I can picture my grandpa picking me up from school. I rush to his car, knowing I would be treated with a snack, and more exciting, one that my parents would not permit before dinner. He smiles softly, rummaging in the McDonald’s brown bag, and presents me an apple pie. I savor its sweetness, and he sips his coffee—a Friday ritual.

But of course, it’s all pretend. I can only envision it so vividly because how frequently I wished it to be true.

I try to remember his loyalty to a McDonald’s breakfast, as my dad recalls fondly. Instead, I hear his angry voice demanding, take me home. He was in fact at home, when I found him having conversations with the banister of the staircase. I also try not to remember when I had first lost him.

“Who are you?” he asked so earnestly.

There was a stillness in that question, punching the realization that someone you love can forget you long before they’re gone.

✴ ✴ ✴

My childhood stuffed animal is irrevocably mine. Legend has it that she was a present for my second birthday. She was an offering wrapped in pastel tissue and promising companionship: a plush, light brown rabbit with long floppy ears, white paws and soles of her feet, and a pink velvet nose. Of course, I have no recollection of this momentous gift, but all the years following, the slow accretion of touch and the thumbprints of childhood pressed into her fur until it dulled into the color of memory. In a way, she held onto more of my early years than my grandpa could; his memory slipped away before his body did, yet the bunny he once carried remembers everything.

She was named Snickers, after my half-sister’s favorite candy. At the age of five, I confused admiration with imitation. Whatever my sister liked, I venerated, even mimicking her restraint. When I noticed she left the tags on her stuffed animals, mid-cut, I abandoned severing the small, fabric Build-A-Bear tag sewn onto the hip of my bunny. With a new and responsible air about me, I ungrudgingly consumed my vegetables first, during dinner that night, so that I could savor my mom’s homemade dumplings last. It was my first act of preservation.

But don’t let my few moments of impressionable restraint confuse you. I was hesitant to ruin her by removing a small tag, yet she served as my default weapon of choice (perhaps because I believed she was inflicting more harm than enduring it). Wielding her by the legs, Snickers was able to deliver a mighty impact against my brother, my small body swinging with the torque of her long ears.

With deep confidence in her practical and reliable use as both sword and shield, and profound attachment to her, I feared nothing more than losing her. So like children do, my youthful imagination theorized a plan of action for irrational cases, such that a burglar provided me the option to take three things with me before letting me go safely. In such a case, I planned to grab snacks from the pantry for sustenance, quickly acquire the emergency cash stashed in my mom’s office, and most importantly, Snickers (oh, and grab my brother if there is enough time).

Back then, my greatest nightmares consisted of losing her to conscientious burglars and to loneliness. “I can’t leave her here for an entire week!” I exclaimed to my parents. Logically, she would wither away from loneliness. And so for a while, my parents carried her for me when traveling, cringing at my tiny toddler stature, which unavoidably dragged her across the dirty airport floor. My priorities did not change, even when I began packing my own belongings for family trips. I was thrilled with the new autonomy; my parents were understandably less thrilled when they opened my suitcase upon arrival to find Snickers occupying the majority, with a few shirts and socks stuffed around her perimeter per her “travel comfort.” Priorities!

The evidence of my developed independence over time, carrying the physical and emotional growing pains of my childhood, was immortalized in the fur I once felt I needed to survive. Every now and then, I am hit with the same panic of losing; perhaps more rational, but just as horrifying as it felt then: noticing my bunny’s nose stripped raw, the silver glimmers of hair that have seemed to multiply since I last saw my parents, or in the pauses between laughter during dinner with my friends, thinking love sounds a lot like them, and how I don’t want them to go abroad next semester. I don’t want to lose them, this moment, or lose what matters.

Unfortunately, it is entirely easier said than done to discern what really matters within a moment. Such fear of loss has likely contributed to my incessant search for nostalgia, or worse, losing the memory of it. Snickers was something that stayed simply because I held her. Likewise, pictures are something that suspend time, just because I want to.

With a whopping 30,000-ish pictures in my camera roll and frequently recorded notes, I feebly attempt to remember everything. Perhaps too frequently. Chronically documented pictures of yesterday’s breakfast or a random sunset, my phone is filled with thousands and thousands of photos that I could look back at, but I often don’t; my notes app, agenda, and loose paper are amassed with thoughts so disparate and fragmented, they effectively serve no use. Futile attempts to preserve memories precisely because sometimes taking a picture feels like a way to keep something close, or to delay a goodbye I’m not ready for.

Actually, I think it’s so I can control the goodbye. So that in case you ever forget, I can show you proof of who I am, display pictures of who I am to you, and who we are together.

At least in accumulating my superfluous archive, I can temporarily fix my constant thirst for nostalgia, and deep fear of forgetting. My second great act of preservation.

In being driven by a fearful preservation, I admit to an infatuation with permanence. Yet this was dismantled upon discovering an unseen photograph, which seemed to rearrange the gravity I had tried to control. In the picture, my grandpa stands facing away from the camera, overlooking a mountainous landscape. He wears a backpack, and in it is Snickers, nestled in the opening. She is essentially unrecognizable, with a lively, fluffy coat and a soft pink nose, and considering her condition, the picture was taken very long ago, long enough ago when my grandpa’s Alzheimer’s had not fully developed. Captured in the same frame are two versions of love I can’t fully remember, nor hardly fathom; it is an eerily comforting scene visualizing a man who I don’t always remember to be kind, but a picture that shows otherwise. Contrary to the horde in my camera roll, I reluctantly accepted what I had always known; I cannot be the holder of all that is true by over-documentation.

I imagine I begged him to carry her. As a child, I managed to make Snickers a responsibility for everyone. Taking her outside to play with me and consequently dirtying her, I pleaded with my mom to wash her safely; when she grew to suffer wear and some serious wounds, I recruited my dad to retrieve his suturing materials from his practice to stitch her up; I bargained with my brother, with genuine promise to be extra nice, if he revealed where he vengefully hid her. The most common responsibility endowed was to keep Snickers’ name a secret (for those lucky enough to meet her).

In such gestures of love that have existed within the seams of my everyday life, in acts of restoration, and in words unsaid, I wonder if this is one of them. I gingerly trace my finger across the sheen of the photograph, trying to remember what Snickers’ little nose felt like then. Trying to imagine. Did he begrudgingly agree to carry her for me? Was she delegated to him by my parents, maybe? This shows he loved me, right?

My grandpa, when his memories were still all his and, unknown to him, was frozen in what seemed to be an act of love. A picture not taken with sore or compulsive desperation to preserve him, but candidly; although he would eventually forget that moment, and eventually me, my grandpa seemed alive and full of love here.

It suddenly becomes unbearingly simple: we know that people, memories, and the particular forms they take won’t last, yet we hold on anyway. We gather fragments, notes, photographs, and even stuffed bunnies. We do so not to outwit impermanence (although I naively believed I could) but to learn live with it. Snickers stayed when my grandpa could not. And still, this photograph proves what all his forgetting cannot undo. He loved me, even if he could not remember how. Even without a name to my face.

What I can tell you is that I have learned that not every stuffed animal, picture, or note means anything. If you have lost someone to Alzheimer’s, you would know. You will feel the anguish, because we are supposed to carry our memories to our last breath, right? It isn’t fair. You will feel the fear, because a lifeless object should not have such life. Impossible. You would theorize a plan of action for the irrational, but also perfectly reasonable case, where I must recall the unidentifiable fat squirrel on the Diag or the receipt I never circle back to, preserving out of fear, and loving by means of control.

The cost of living is to later forget, and the cost of loving is to do so fearlessly; fearlessness not in vain because love transcends, where Snickers embodies love’s permanence without a living pulse. Because this picture confirms every scenario I ever feigned, every imagined memory I craved in which my grandpa loved me.

Snickers is irrevocably mine. Worn in her tattered coat, she has absorbed every iteration of comfort I could not name because it is entirely easier said than done to discern what really matters within a moment. I don’t know if I can say that about much else. She is far too frayed, making her unsuitable and, by extension, probably bizarre to be passed down as a family heirloom. Yet in a way, Snickers holds the power of a family heirloom, like a conduit of generational tenderness.

And while I have my friends, my boyfriend, my parents, or my family, they are hardly just mine. People beautifully belong to no one really, though they can be reduced to labels, as our hearts beat for many and for a multitude of reasons. While my bunny’s Build-A-Bear heart, inserted upon her inception, does not beat, it has rested against mine during many sleepless nights. On such nights, when the darkness was somehow not dark enough and anxiety kept me awake, I would cast her long, floppy ear over my eyes and fall asleep in a way only my mom would shield my eyes when I napped as a child. Each morning, I place her neatly as the final touch on my made bed, in the middle in all her glory, and in front of my throw pillow, sure to let her breathe; I am not sure, but I would like to imagine my grandpa doing similarly in the moments leading up to that picture, where Snickers is comfortably carried, her head positioned to let her breathe.

December Education Edit

As research on Alzheimer’s continues to evolve, new findings are reshaping the way we understand memory, aging, and care. This month, we’ve highlighted several short, accessible videos that break down the latest discoveries.

December Service Edit: Alzheimer’s Advocacy

By: Jenny Medrano

Alzheimer’s Advocacy

Innovative research, transformative care, and needed support, are all critical components to the collective fight against Alzheimer’s. As important as these solutions are, equally important is the funding and coordination made possible through government intervention. In the U.S., Congress plays a significant role in ensuring public policies are put into action that connect Americans to Alzhemier’s solutions.

While the burden of this responsibility falls on our elected policymakers, it’s also our responsibility to push them to act on it. In addition to caring for the people in our own lives affected by this disease, we can also take action to ensure Congress is actively prioritizing the needs of the Alzheimer’s community.

Here are some specific initiatives you can help support in just a few small steps:

Advocate for Increased Alzheimer’s Research Funding

Click here to support an initiative that would allocate $113.485 million in 2026 to Alzheimer’s and dementia at the National Institute of Health. This iniative would also contribute $35 million to the implementation of BOLD Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—an act that supports the cause through a strengthened national public health framework. Learn more about BOLD here: BOLD Infrastructure for Alzheimer's Act.

Urge Congress to Support the ASAP Act

Click here to push Congress to pass the bipartisan Alzheimer’s Screening and Prevention Act (ASAP) which would increase early and accurate dimensia diagnoses in the U.S. The diagnosis timeline is essential in determining both the patient’s overall quality of life and financial burden. Even still, the Alzheimer’s Association estimates that up to half of the 7 million Americans living with dimentia remain without a formal diagnosis. This act will carve out Medicare coverage of FDA approved blood biomarker screening tests, significantly improving upon this current shortcoming.

Help Support Workforce Preparation

Click here to support the Accelerating Access to Dementia & Alzheimer’s Provider Training (AADAPT) Act which would help improve primary care providers’ ability to care for patients with dimentia. The AADAPT Act will fund virtual training and education, and support programs that address knowledge gaps and build the workforce capacity required by providers who are the first point of contact for essential Alzheimer’s care.

Volunteer in Alzheimer’s Research

Click here to search for clinical studies and trials close to you or online. Volunteering to participate in Alzheimer’s research is one of the most meaningful and tangible ways you can take action to support the cause. In order to make innovative research possible, researchers require a large participant base of many types of individuals to produce meaningful results. Read here for more information regarding clinical research participation: FAQs.

Works Cited

Alzheimers.gov, https://www.alzheimers.gov/. Accessed 30 December 2025.

“Advocate.” Alzheimer's Association, https://www.alz.org/get-involved-now/advocate. Accessed 30 December 2025.

“BOLD Infrastructure for Alzheimer's Act | Alzheimer's Disease Program.” CDC, 26 June 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/aging-programs/php/bold/index.html. Accessed 30 December 2025.